‘What did I do wrong? Why is she treating me this way? I don’t understand!’ my brother lamented, his voice quivering; his blue eyes pained; his face red from stress.

His partner was out to ruin him in every way possible. She accused him of child sex abuse and deprived him of his income. Yet he still had to pay child support. Then, there was the long trawl through the criminal and family court. She milked the system for all it was worth, while he genuinely had no idea what he had done.

‘I was trying to help,’ he continued.

Helping was my brother’s way of loving. From childhood, he had been obliged to play the hero, handling our mother’s worries; acting as surrogate father to his younger sisters; or stepping in as the extra man in the house whenever my father required it, be it by providing additional muscle in the garden or by paying the milk bill with his part-time earnings. A gifted music teacher, he had spent his adult life realising his students’ potential. His relationships were marked (and marred) in the same way.

‘I believe you have Jane Bennet Syndrome,’ I observed.

‘What do you mean?’

Odd that he should ask that question, I thought. My brother is very literary.

‘I mean, you have a disordered tendency to see the good in others.’

Jane Bennet, Jane Austen’s beloved character from Pride and Prejudice, epitomises goodness. Being truly good - and sensible because she is truly good - she nevertheless cannot comprehend flaws. As her sister Elizabeth, who aspires to truth (but whose capacity for truth is compromised by personal bias), observes, rightly here, because she loves:

"Oh! you are a great deal too apt, you know, to like people in general. You never see a fault in anybody. All the world are good and agreeable in your eyes. I never heard you speak ill of a human being in your life."

Jane replies, in all honesty:

"I would not wish to be hasty in censuring anyone; but I always speak what I think."

To which Elizabeth responds:

"I know you do; and it is that which makes the wonder. With your good sense, to be so honestly blind to the follies and nonsense of others! Affectation of candour is common enough – one meets with it everywhere. But to be candid without ostentation or design – to take the good of everybody’s character and make it still better, and say nothing of the bad – belongs to you alone."

– Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice, Chapter 4.

Jane Bennet Syndrome

Jane Bennet Syndrome has the following characteristics:

blindness to folly and nonsense

complete naivety regarding others’ vices and flaws

over-emphasis on others’ good character, whereby one improves upon or exaggerates the good perceived

the desire to realise goodness, to strive for a noble ideal, which can bring out the best in everyone.

Such an outlook is bound to lead to suffering, for not all share this desire for goodness; or their idea of goodness is corrupt in some way. Jane Bennet suffers at the hands of the haughty, affected Bingley sisters whose proud opinions, along with Darcy’s cynicism (he assumed Jane’s interest in Bingley was contrived), obstruct her possible future happiness with Bingley. In the end, however, Jane’s virtue is rewarded. She marries the man she deeply loves.

Sadly, this is not always the case in real life. And this is why I call out Jane Bennet Syndrome.

I’ve suffered from it, myself. I bought our family home under the influence of Jane Bennet Syndrome. True, it was what we could afford at the time; but I did see potential in that down at heel, mid-century bungalow, and completely failed to realise the toll it would take on our family well-being and my coping ability. Our growing family nearly ruined that old house; and that old house nearly ruined us. Fortunately, we were able to do it up, and now enjoy a beautifully renovated space.

Virtue rewarded? My husband likes to think so.

He, too, bless him, has Jane Bennet Syndrome.

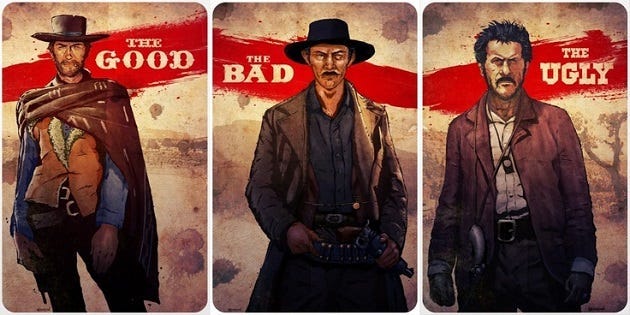

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

Not long ago, I had a brief conversation with Substack writer Tiffany Chu about facing trauma through writing. Some people confront it head on. Others approach it more indirectly, sometimes unwittingly. I fall into the latter category. I have developed characters that reflect my desires or dreams more than reality. They have provided tremendous comfort. In A Distant Prospect, I created the father I wanted to have, who was nothing like the father I had; and the music teacher who believed in and nurtured her students, whereas my school music experience had been dominated by a narcissistic bully. Writing about how you want things to be, however, is therapeutic. Dreams and desires gently probe the wound. In doing so, they make you aware of what you deeply value. When that happens, growth and healing can follow.

Certainly, a purpose of art is not only to show what is, but also what could be. As Dostoyevsky states in The Idiot:

Beauty will save the world.

Beauty is born of truth and goodness, of that which ‘is’ and that which is desired. If either is lacking, then so is beauty. Truth, however, embraces the bad and the ugly; and yet it cannot neglect the good, for that, too, is true. Beauty, then, is the child of a curious marriage between the real and the ideal. Art, being concerned with beauty in one way or another, enters into that relationship.

This means embracing the mess and hoping for the best.

One of my primary motives for writing is problem solving. It’s my way of fixing things. In fact, my brother’s traumatic divorce induced me to begin writing In the Hearts of Kings. I don’t deal directly with personal experiences. It’s too painful. In fact, this Substack post is the first time I have ever written explicitly about one such experience; and I hesitated to do so. Instead, I transfer experience to a safe space: other characters, another period, an entirely different situation. There, I explore the essence of the problem.

In this instance, the problem was, for me:

How do you deal with something outside your capacity to solve - for which your personality, means, abilities, circumstances, and station in life leave you poorly equipped - but which affects you deeply, because it involves people you love.

Do you put it behind you and move on?

Do you fight it?

Cover it up?

Transcend it?

Distance yourself from it?

What do you do?

Well, one thing you need to do, when writing a novel about such problems, is to embrace the mess.

Messy Medea

My youngest son recently developed an interest in Greek tragedy. He had to read Aeschylus’ Oresteia for his liberal arts course and write an essay on it. It was his first essay, and his first real taste of drama.

It also meant that I, too, had to read the Oresteia.

It’s been a long time since I have read Greek tragedy - I read Oedipus Rex just after finishing school. Reading the Oresteia, I was impressed by the humour, the word power, and the bold exposure of human foible.

I then read Euripedes’ Medea, which has been on my reading list for a while. Why? Because Darius Milhaud’s Medée was the last opera to be performed at the Paris Opera before the Germans entered Paris in June, 1940. You can listen here. In fact, distant canon could be heard during the final performance of 15 May that year. So, it was pertinent to Outside Heaven’s Sway.

It’s also a revenge tragedy, which is highly relevant as far as themes are concerned.

The poetic realism of Euripedes’ drama is absolutely gripping. Medea and Jason are a jaded middle-aged couple, grown apart. Each follows a separate trajectory, with disastrous consequences. Jason, indifferent to Medea, despite her prior assistance in his quest for the golden fleece, and despite the fact that she has borne him children, is determined to abandon Medea in order to pursue an advantageous marriage to Glauce, daughter of King Creon of Corinth. Medea, who is still slavishly obsessed with Jason; and who had already overstepped the mark in pursuing Jason in the first place; refuses to be abandoned, and again goes too far with her hideous revenge.

The Greeks excel at showing us how we are, and how choices bind us to our destiny.

To which the Jane Bennets among us will protest, crying, ‘No, we’re not like that at all! It cannot be that way!’

Literary Leech Gathering

Medea, for me, contains important literary lessons:

write characters as they are, not how you want them to be

have them do what you do not want them to do

don’t try to fix it

express deep truth, be it physical, emotional, moral, or philosophical, with clarity and imagination.

Broken Bits

The good in literature - that which is desired - is sometimes outside the central action. It can be hidden, in a subplot maybe, or in a supporting character.

Sometimes it’s the gold which binds all the broken, flawed bits together.

A lot of Japanese ideas get floated these days. Kintsugi, the art of transforming broken pottery into new pieces, entertained a brief social media interest before Marie Kondo threw everything out.

I love the idea of Kintsugi. And I think it applies to writing.

Writers pick up the broken bits of humanity and refashion them; they bind them with golden themes and insights, and create a piece with flaws exposed, but curiously decorated.

The good, the bad, and the ugly combine to create a thing of beauty…

Which is a joy forever.

When I was young, all the way through high school, I too saw the good in people, and just ignored the bad, telling myself their apparent and clear bad faults were not important and did not characterize such persons. I am not here talking about situational moral failings, which we can all succumb to, but fatal character flaws such as greed, narcissim and arrogance or hubris.

Ignoring such was both naive and dishonest on my part; it was reading through great literature, including all of the Russian greats and all of George Eliot's novels (sorry, I prefer her to Austen or even Dickens among English writers) while pursing a degree in journalism and Eng. Lit, that I learned a lot about myself.

I had an epiphany; it was not that I thought people were good. It was that I thought that if I had acted as if people were good, they would act accordingly. This never was confirmed as true, other than in my imagination.

This epiphany happened 30 years ago. It was literature that helped me enter that realm of where I saw reality and could live with it. Humans behave in all kinds of ways--good, bad and ugly. Most of us fit into this category.

Literature also taught me much about humility, and the Greek tragedies about hubris. I will end here by saying that I hope your brother sorted things out.

I applaud you for this, Annette. Your post reminds me of the book I'm currently reading by Joanna Penn, "Writing the Shadow," which is about channeling our inner darkness into our writing without shying away from it. I'm learning to write the things that scare me, because I think those are the parts that need a light shone on them. Thank you for sharing this. Wonderful post!